Teacher Salaries

State Special Education Workers Are Underpaid in Missouri.

By: Lexie Stoker, Falyn Page, Miko Qian, Yang Sun

COLUMBIA, Mo. — All special education teacher Debbie Muro would have to do to get a $17,000 raise is take a job at the public school across the street.

Muro teaches at Delmar Cobble School for the Severely Disabled in Columbia, one of Missouri’s 34 state-funded schools for children with severe disabilities. In Missouri, working for one of these schools instead of a traditional public school almost always means taking a pay cut.

Educators working at these schools, which operate as a district called Missouri Schools for the Severely Disabled, are sometimes paid more than $15,000 less than their equally qualified counterparts working for other public schools in Missouri.

Muro has a master’s degree and 15 years of teaching experience. Someone with those qualifications earns about $35,000 per year at a state school for severely disabled children. At Parkade Elementary School, a teacher with a master’s degree and 15 years of experience earns nearly $53,000.

“The pay is always in the back of your mind,” Muro said.

According to the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, the median salary for the 2015-2016 school year for Columbia Public School teachers was more than $46,000. Teachers at Delmar Cobble School made a median salary below $30,000.

The problem exists because of where the funding for these two types of schools comes from. Public school districts secure funds from property taxes, state funds and federal funds. State special education schools only rely on state funds.

“If these state-run schools’ payment is well below a surrounding public school district, they are going to have difficulty,” MU economics professor Michael Podgursky said.

In other states, special education is integrated into public schools, or it operates privately. As part of the state budget, Missouri state special education schools are subject to funding changes.

For the 2015-2016 school year, the Missouri Schools for the Severely Disabled requested $2.7 million to increase salaries. Governor Jay Nixon granted $1 million of that request. However, by the final budget, that amount had been reduced to $300,000, a fraction of the initial request.

“We don’t get to collect property taxes or do a levy; it’s state funding, these are state employees. ” said Sarah Potter, communications coordinator for the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. “With salaries so low, people don't have to stay. They can go other places and make more money.”

Donna Catt, head administrator for the Delmar Cobble School, understands the effects turnover can have.

“We had a 20 percent turnover in staff within a 5-year period for every year,” Catt said. “The hardest thing was the attrition rate wasn’t being replaced fast enough by certified personnel.”

Still, there’s a reason why special education schools operate differently than public schools. The education involved is specialized, so separate schools accommodate a variety of needs better.

“What we do here is a splinter that is extremely specialized for children,” Catt said. “It would be better to become more intensely focused on the schools we do have.”

Despite the lower pay, many teachers continue to work and seek out positions at state special education schools.

“I think that these kids need service, and they need a good teacher, and they need people in their lives that care about them,” Muro said. “Right now I feel like I’m providing that.”

Still, Muro said the funding gap has effects that extend into the classroom.

“If they did give us more funding, it would benefit the kids, and then you would attract more teachers,” Muro said.

Gretchen Hein-Roberts’ son, Blake, attends Delmar Cobble School. Blake lives with severe disabilities. He has cortical vision impairment, cerebral palsy and uncontrolled epilepsy. He is in a wheelchair and uses a communication device to talk. Hein-Roberts says teacher turnover affects her child’s education.

“As a parent I do notice a lot of staff turnover at times. We had a P.E. teacher for the last two years, and now we have a new P.E. teacher, and before that we had a different teacher.” Hein-Roberts said. “Having constant turnover, there’s no consistency at all.”

Low salaries for state employees are a problem across departments, not just for teachers in Missouri Schools for the Severely Disabled.

Missouri is known for having the lowest-paid state employees, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2011, Missouri public employees were at or near the lowest pay in every industry sector the Census Bureau tracked.

For teachers working in Missouri Schools for the Severely Disabled, this means the path to higher wages is long and slow.

“We hope that, with the next budget, we can raise our teachers’ salaries to be commensurate with local area pay so that we are not having staff leave and go to other jobs in other areas where they can make more money,” Potter said.

The topic won’t be up for discussion again until the next legislative session.

Donna Catt, the building administrator for Delmar Cobble School for the Severely Disabled, talks about how state-funded special education schools struggle to retain their teachers in Columbia, Missouri, on Tuesday, Nov. 1, 2016. Catt said Delmar Cobble School has had a 20 percent turnover rate every year for the past five years.

Artwork painted by students decorates the wall of Delmar Cobble School for the Severely Disabled in Columbia, Missouri, on Tuesday, Nov. 1, 2016. Building Administrator Donna Catt said the pay gap between state-funded special education teachers and public school teachers is a problem.

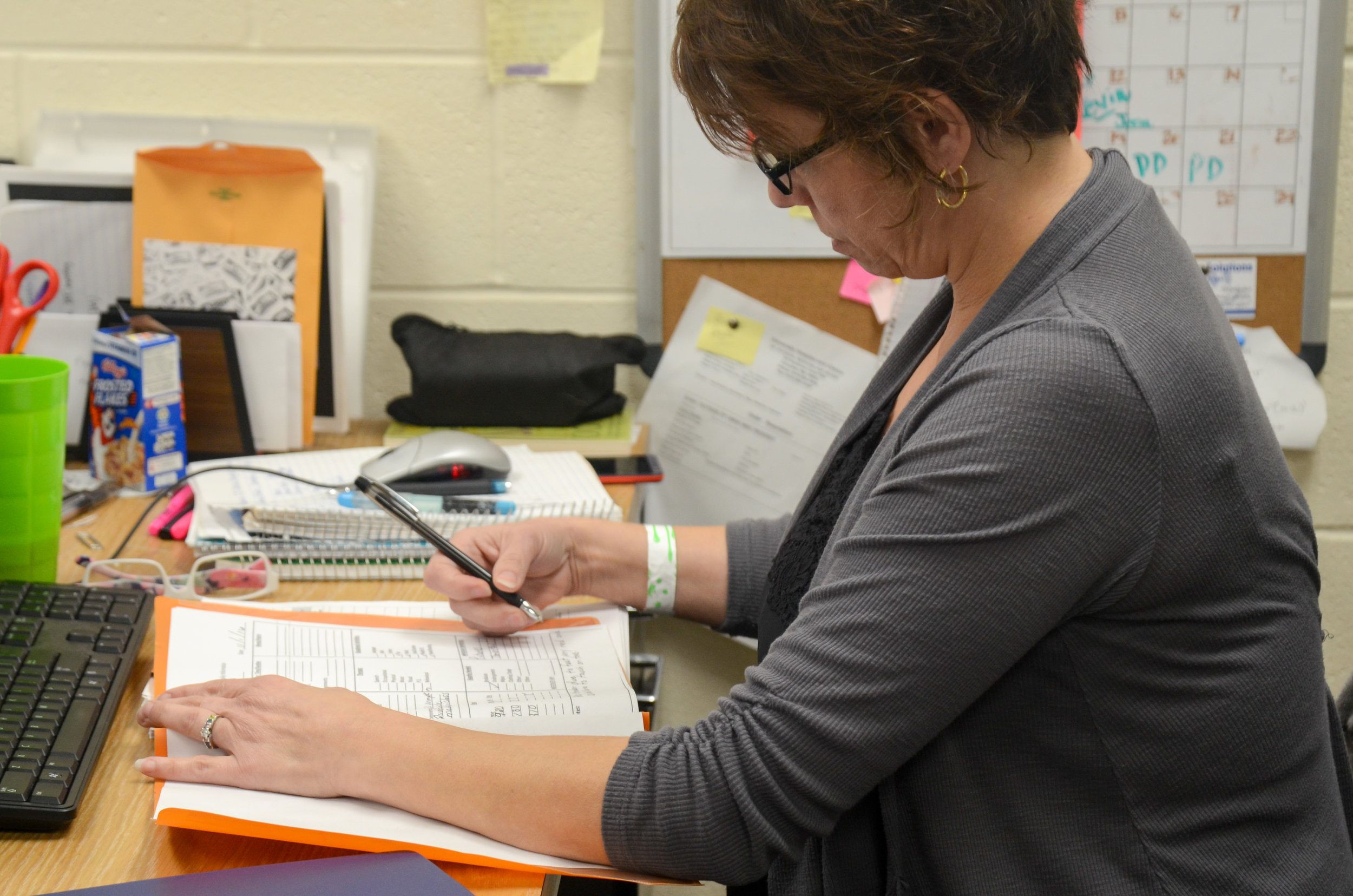

Debbie Muro, a teacher at Delmar Cobble School for the Severely Disabled, records the time when she changes her students’ diapers in Columbia, Missouri, on Tuesday, Nov. 1, 2016. Muro said she does a lot of paperwork in order to provide proper care for her students.

Gretchen Hein-Roberts relaxes and massages her 12-year-old son Blake’s hand in Columbia, Missouri, on Monday, Oct. 31, 2016. Gretchen said that Blake has multiple severe disabilities, and is concerned about her son developing relationships with his teachers when there is high turnover.

Gretchen Hein-Roberts holds her 12-year-old son Blake’s hand in Columbia, Missouri, on Monday, Oct. 31, 2016. Gretchen said that she is frustrated by high turnover at Delmar Cobble School for the Severely Disabled.